On Friday evening, November 1, 1918, a Brooklyn Rapid Transit subway train left the Park Row station in Manhattan, ran east across the East River, then south through Brooklyn. At 6:42 p.m., it crashed near the intersection of Malbone Street, Flatbush and Ocean Avenues; 93 people died and hundreds were injured. It was the deadliest transit disaster ever in New York City. 14 of the victims are interred at Green-Wood Cemetery.

One of the lyrics in the hit musical “Hamilton” is “who will tell your story?” Part of our mission at Green-Wood is doing exactly that: telling the stories of many of our 570,000 permanent residents. Central to Green-Wood Cemetery’s design is memorialization–that gravestones mark graves, allowing the living to visit, commemorate, and honor individuals who are interred there. It is in that spirit of memory that we honor–and remember–the victims of the Malbone Street Wreck, 100 years later.

As Green-Wood’s historian, I knew that our chronological books, which list all burials performed between 1840 (when burials started at Green-Wood) and 1937, would be very useful in determining if any of the Malbone Street Wreck victims are interred at Green-Wood. Checking those books, starting at November 1, 1918, I discovered that 14 individuals were indeed interred at Green-Wood, based on the causes and places of death recorded, I followed up by researching these people online. Their stories give us a better understanding of the 93 people who lost their lives in that crash.

Who were these people? By and large, they were working class Brooklynites, returning home, on the Brighton Beach Line, to their families on a Friday evening in the fall. Those interred at Green-Wood ranged in age from 18 to 54. Most of them lived in Flatbush and Ditmas Park; they would have been home in just a few minutes if all had gone well. But most certainly all did not go well.

There were other problems in the world on the evening of November 1, 1918. The World War–“the war to end all wars”– was still raging in Europe. It was reported that day in the banner headlines of New York’s newspapers. The influenza pandemic continued to claim many lives, day after day. And a strike of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers on the Brooklyn Rapid Transit line–privately owned at the time–had just begun. So a dispatcher by the name of Edward Luciano was given the briefest of classroom training on how to operate a subway train and was handed the throttle of that ill-fated train. Luciano soon demonstrated his incompetence, overshooting the platforms of several stations in Brooklyn. And when it came time to navigate an underground S-curve at Malbone Street (renamed Empire Boulevard in the wake of this tragedy), where Malbone intersected with Flatbush and Ocean Avenues, his incompetence turned deadly. Going at least 30 miles an hour in a 6-mile-an-hour zone, he crashed the 5-car train; the wooden cars, within seconds, splintered and shattered. The greatest tragedy in mass transit had come to Brooklyn.

For those interred at Green-Wood, the cemetery’s records list the cause of death for most of them as a fractured skull. One died of a “fractured chest”–another’s cause of death was listed as “accident.”

Here are the names of those who were interred at Green-Wood, in the order of their interment:

Louis Hopkins

Frederick Minton

Margarette Sullivan

George Holmes

Addie Pilkington

Harold Schaefer

Wright Silas Mussen

Ferdinand Rothe

Alexander Palmedo

David Kerr Jr.

John Enggren

Edward Erskine Porter

Bessie Love

Raymond Lewis Payne

Through Green-Wood’s records, and the miracle of the Internet (particularly though Ancestry.com for portraits of the victims, their census records, draft registrations, etc.), I have been able to find information about each of these individuals.

Louis Hopkins, as per the 1910 census, was 48 years old, lived with his wife Maud and his teenage daughter Marion at 2031 Bedford Avenue, and managed a life insurance company. He had attended Yale.

Frederick Minton was the oldest of those interred at Green-Wood; he was 54 when he died. He was born in New Jersey and lived at 398 East 18th Street with his wife, Lillie. He was a credit manager. As per the 1915 New York State census, their two children, Fred and Gertrude, in their 20s, lived with them. Minton was well-off–he left an estate of $25,000–the equivalent of $418,000 in 2018.

Here is the biography of Margarette Sullivan that I have composed, based on my research:

SULLIVAN, MARGARETTE (1899-1918). A native New Yorker, she lived at 2745 Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn with her parents, two brothers, and three sisters. She was just 19 years old when she died. Lot 5499, grave 1735.

And here is another:

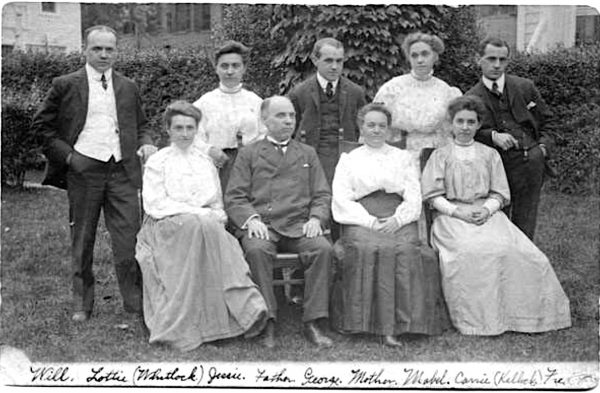

HOLMES, GEORGE WHATELY (1883-1918). Born in Flatbush, he lived at 661 Westminster Road in Brooklyn. He worked in his family’s manufacturing firm, F.W. Holmes & Sons, on Pearl Street in Manhattan. His parents, two brothers, and four sisters all lived in Brooklyn. In 1908, he married his wife Ethel. According to his World War registration, bearing his signature, he described himself as short, of medium build, with gray eyes and black hair. Section 131, lot 35125.

Addie Pilkington was 36 years old and was living with her parents and three siblings at 214 Webster Avenue. She worked as a stenographer.

Harold Schaefer was just 18 years old when he died. He lived with his parents and two brothers at 2804 Farragut Road. In the last two years of his life, he had worked as a clerk, electrician, and tent maker.

Born in Manhattan, Silas Wright Mussen was just 25 years old when he died. He had been married for three years to his wife Jennie. They had a baby daughter and lived at 402 Ocean Avenue. He worked as a drug store clerk.

Ferdinand Rothe was the only immigrant of these individuals interred at Green-Wood (all the others were born in the New York metropolitan area). Born in Germany, he was 41 years old. He and his wife Sarah had a 6-year-old son and lived at 316 East 19th Street. He left a modest estate.

A native of Brooklyn, Alexander Palmedo was a veteran of the Spanish-American War, having served in Troop C of the New York Cavalry. He married his wife Elizabeth in 1899; they had one child. They owned their home at 439 East 19th Street, on which they held a mortgage. He was a merchant, a Mason, and a member of the Spanish-Americans veterans. He was 50 years old when he died.

Born in Manhattan, David Kerr Jr. was 34 years old when he died. His parents were Irish immigrants. He was survived by his wife Ethel and his son David, with whom he had lived at 1448 35th Street. His assets totaled $250; his primary asset was his legal claim for wrongful death. His father had served in the Civil War. David was a electrician.

John Enggren was born in New York City to immigrants: a Swedish father and an English mother. He and his wife Lucy married in 1906; they had two sons and rented at 37 East 10th Street. He worked as a clerk in a commission house. He left an estate of $3000, the equivalent of $50,000 in 2018.

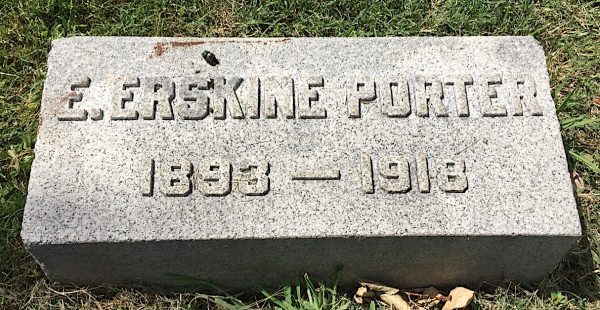

The headline on the front page of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of November 2, 1918, reported Edward Erskine Porter’s death. Here’s his biography:

PORTER, EDWARD ERSKINE (1893-1918). Born in White Plains, New York, he attended Brooklyn Polytechnic School, where he ran on the track team and had a “bright stage career,” writing the honor society’s theatrical performance, “In Disgust,” a “great success.” In his World War draft registration, he described himself as tall, of medium build, with blue eyes and light hair. He was a graduate of Williams College, class of 1915, where he had headed the debate team. At the time of his death, he lived at 309 Caton Avenue in Brooklyn with his wife, Eloise, whom he had married a year earlier in Savannah, Georgia, and their baby daughter. He was in the bond business at 56 William Street in Manhattan. Porter was in the first car of the train that crashed at Malbone Street–it was that car that absorbed much of the impact when it hit the subway wall; many of the dead were in that car. His father, a prominent real estate broker, checked that evening with Porter’s wife and learned that Edward had not come home. The father then went to the hospital where the wounded had been taken. Not finding his son there, he walked into the adjoining morgue, where, sadly, he discovered his son’s remains. Section 190, lot 35123.

The building where Porter and his family lived still stands:

Bessie Love was only 20 years old when she died. Her address was 90 St. Marks Avenue.

Raymond Lewis Payne was the last of the victims to be interred at Green-Wood. He had been cremated; his ashes were interred on November 17. Here is his biography:

PAYNE, RAYMOND LEWIS (1899-1918). Born in Brooklyn, he lived there for his entire life. Payne worked as clerk for R.H. Donnelly on Fulton Street in Manhattan. He registered for the World War draft just a month before he was killed. In that draft registration, he listed his home address as 1212 Avenue H in Brooklyn, where he lived with his parents and his sister. He described himself as short and slender, with brown eyes and hair. He was just 18 years old when he died–the youngest of the victims who are interred at Green-Wood. After his death, his draft registration form was crossed out with this notation: “cancelled deceased.” Section 4, lot 33035.

On November 1, 2018, 100 years to the day after the Malbone Street Wreck, a commemoration was held along Flatbush Avenue, on the edge of Prospect Park, just north of where the crash occurred. It was organized by the Brooklyn Borough President’s Office and Ryan Lynch, that office’s director of policy. Borough President Eric L. Adams, Chief Executive Officer of the New York City Transit Authority Andy Byford, FDNY Chief of Department James Leonard, and other community leaders spoke.

Three historians talked about the tragedy: Ron Schweiger, Brooklyn’s historian, talked about the crash and its historic context, Concetta Bencivenga, executive director of the Transit Museum, spoke about the crash and the safety changes that were made in its wake, and I told the stories of those interred at Green-Wood who died that day. The memorial wreath pictured above was then carried to the nearby Prospect Park Subway Station, where it was displayed for the day. The next day, it was brought over to Green-Wood and placed at the adjoining graves of two of the victims, Bessie Love and George Holmes.

One hundred years later, we remember all of those who died so suddenly and so tragically in the Malbone Street Wreck.

This is really interesting and I’m glad I stumbled upon your site while doing some family research. One small correction for Silas Wright Mussen: He and Jeanette actually had a 2-year-old son, not a daughter, named William Mussen. I’m Silas’ great-grandson.

One other interesting local connection, though related to Silas’ wife, Jennie, rather than Silas himself. She was the sister of William B. Atwater, who, as best as I can tell, was a somewhat well-known pilot in the early aviation scene around Long Island.

Thanks so much for your comment. Always great to hear from a descendant–and to learn more information from him or her.

I’m glad that I stumbled upon this page, while looking for additional information about the Malbone St. wreck. Such a great tribute to the victims of this tragedy.

Being a huge fan of the NYC Subway, I wanted to offer a few corrections about the rapid transit aspect:

BRT trains that served the Park Row Terminal in Manhattan crossed the Brooklyn Bridge and served on the Brooklyn elevated lines, not in subway tunnels. The site of this accident is currently on the Franklin Ave. Shuttle route (just before the Prospect Park station on the Brighton Line). A century ago, this route diverged from the Fulton St. elevated line at Franklin Ave.

(Note: In the 1930’s the city-owned Independent Subway (IND) built the Fulton St. subway line — used by the current “A” route. This rendered the EL obsolete. It was mostly torn down after unification.)

This accident bankrupted the BRT, which exited bankruptcy in 1923 as the BMT (Brooklyn Manhattan Transit). Back then, the BRT and the IRT were competing private companies, joined in competition during the 1930’s by the IND. (The system as we know it today was unified in 1940.)

Something else about the crash. The first and fourth cars of the train did not suffer nearly as much damage. (The fifth car was not damaged.) The second and third cars had severe damage. Mr. Luciano, the unqualified Motorman actually survived the accident and was at his home when the Police caught up with him hours later

(Also, the Motorman’s strike ended, due to this accident.)

Here’s a photo of the first car, from a news article, showing the relatively minor damage:

https://brooklyneagle.com/articles/2019/11/01/malbone-street-train-wreck/