Green-Wood stories–and my blog posts–touch upon many diverse topics. But I never thought that I would be blogging about Russia.

I am usually out on the cemetery grounds a few times a week. With 574,000 interments, 7,000 trees, and tens of thousands of gravestones, there is so much to see! Sometimes I notice, for the first time, things that have been out there for a century or more. And sometimes I see things that are recent additions to the grounds. That was the case when I was recently out on Meadow Avenue, to mark the grave of a Civil War veteran for the installation of his Department of Veterans Affairs-issued gravestone. Looking at the Hill of Graves, and the cluster of public lots there, it soon became apparent that something had changed. As I observed, the hill in Public Lot 8999 was dotted with newly-installed granite, slant-front gravestones. And each of them had what I recognized as a Russian flag next to it. That was different!

So I was off to the Internet for answers as to why these gravestones, so many years after these interments, had been placed at these graves. The first clue came from the website of the Russkiy Mir Foundation, which headlined on October 31, 2018, “Sailors of the Imperial Russian Navy Commemorated in New York.” The report continued (text is as it appeared online in somewhat strained English):

The sailors of the Imperial Russian Navy has been honored in New York, TASS reports. The solemn ceremony was held on October 31 at one of the city cemeteries. Navy lieutenants Mikhail Desyatov and Alber Grippenberg are buried there. Flowers were brought to their graves by children who study at the school under the Russian permanent mission to the UN.

. . .

The grave of Lieutanant Desyatov was one of the first Russian military graves in the United States which got certification from the representative office of the Russian Defense Ministry.

A second report on the same website, published on January 1, 2019, was headlined: “Another Sailor of Imperial Russian Navy Identified and Buried in USA.” It reported,

Ministry of Defence has ascertained the name of another Russian sailor buried in the USA, TASS informs.

Through research, it was found out that the grave of Stepan Billy is located in the historical Greenwood Cemetery. Seaman was crew member of Alexander Nevsky frigate. He died on September 26, 1863 and was buried in Brooklyn.

As Russkiy Mir informed, Ministry of Defence representatives on organizing and maintenance military memorial work in the United States found out earlier that graves of six soldiers are located at one of New York cemeteries. Their names are figured out as well. Five of them were crew members of Alexander Nevsky, Peresviet and Oslyabya battleships. These ships were in the squadron that Russian authorities sent to the US coast during the years of Civil War of North and South.

So there you go!

I was familiar with photographs of a Russian fleet anchored in New York Harbor during the American Civil War. It turns out that there is plenty online about that visit. When President Abraham Lincoln took office early in 1861, there was one huge problem facing him: how to deal with the Southern states that had seceded from the Union. Four long years of Civil War would soon follow. Lincoln received no support from the monarchs of Europe, who opposed the United States’ experiment in republican, monarch-free government. But Russian Czar Alexander II faced a predicament similar to Lincoln’s–Poland, a part of the Russian empire, was threatening to secede from it. So Russia, in addition to taking on the Poles, dispatched its Atlantic Fleet to visit New York City, in a show of support for a strong central government, free of secession.

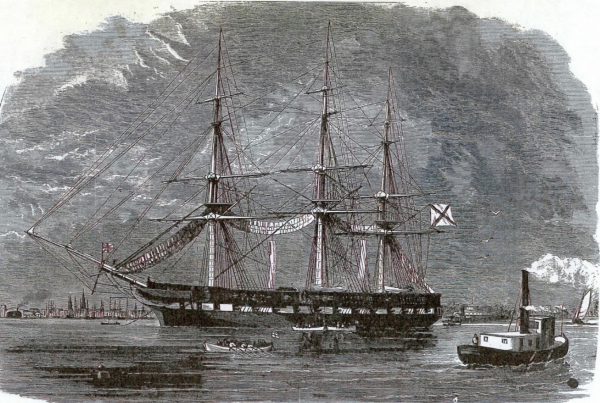

On September 24, 1863, the Alexander Nevsky, a screw frigate of 51 guns, and the Perseviet, a frigate armed with 48 cannon, arrived in New York Harbor. Within weeks, five other Russian ships, including the Oslyabya (carrying 33 8-inch guns and 450 sailors and marines) had arrived. Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, wrote enthusiastically in reaction:

The Department is so much gratified to learn that a squadron of Russian war vessels is at present off the harbor of New York, with the intention, it is supposed, of visiting that city. The presence in our waters of a squadron belonging to His Imperial Majesty’s Navy cannot but be a source of pleasure and happiness to our countrymen. I beg that you will make known to the Admiral in command that the facilities of the Brooklyn navy yard are at his disposal for any repairs that the vessels of his squadron need, and that any other required assistance will be gladly extended. I avail myself of this occasion to extend through you to the officers of His Majesty’s squadron a cordial invitation to visit that navy yard. I do not hesitate to say that it will give Rear Admiral Paulding very great pleasure to show them the vessels and other objects of interest at the naval station under his command.

Welles also would write in his diary, “In sending them to this country there is something significant. What will be its effect on France and the French policy we shall learn in due time. It may be moderate; it may exasperate. God bless the Russians.”

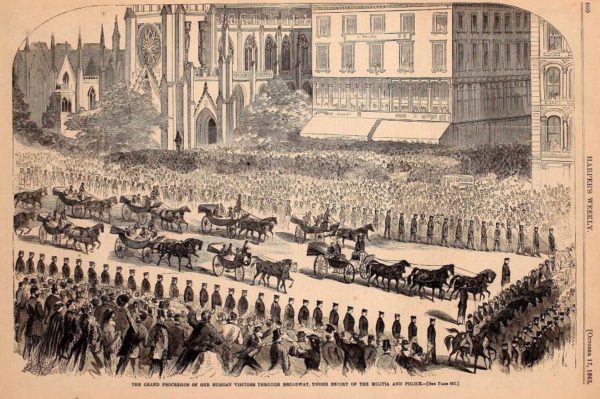

New York City greeted the officers and sailors of the Russian fleet with great enthusiasm.

It was not just the military, and members of the Lincoln administration, who were thrilled by the visit of the Russian fleet. New York City’s mercantile and social elites rejoiced at the visit of these exotic sailors.

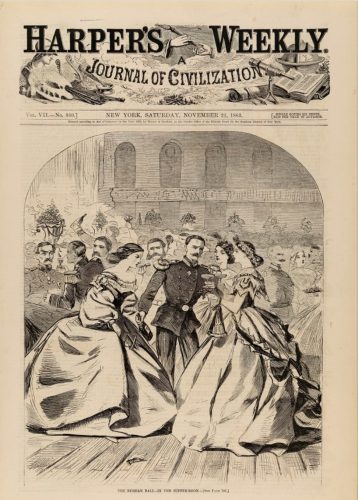

Soon after the arrival of the Russian fleet, a banquet was held in its honor at the Astor House, hosted by business leaders. And a society ball soon took place at the Academy of Music on 14th Street in Manhattan.

The Russian fleet, and its sailors, would remain in New York Harbor into 1864. And, invariably, some of them would die in New York–and be interred at Green-Wood.

Circa 1865-1870, the American Bank Note Company produced the graphic design below, showing the pantheon of American leaders: Abraham Lincoln, U.S. Grant, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington (the last two, a bit more removed in time, got only small corner images). But the central figure in this design was Alexander II, who had freed the serfs of Russia–and had supported the Union by directing the visit of the Russian fleet to New York City (and another fleet to San Francisco):

When I recently visited the graves of the Russian sailors, each was marked with a granite stone describing and naming the ship that man had served on, his rank, and his life dates. Here is one of the 11 granite markers; the others are identical in design and material, but vary in the particulars of the inscriptions:

In all, there are 11 seamen now memorialized at Green-Wood by these new gravestones. They are Sailors Yakov Ozhimkov (1823-1864), Stepan Biliy (1823-1863), Indrik Ratik (1825-1864), and Yusup Khalimov (1830-1864), as well as Warrant Officer Nikolay Borodovkin (1842-1864), all of whom served on the Imperial Russian Navy Frigate Alexander Nevsky, Sailor Ivan Kuznetsov (1939-1863), who served on the Imperial Russian Navy Corvette Varyag, Sailors Peter Poromov (1825-1863), Avdei Semonov (1828-1863), Ivan Dianov (1832-1863), and Fedor Kirolov (1829-1863), all three of the Imperial Russian Navy Frigate Peresvet, and Sailor Mikhail Khudobin (1842-1864) of the Imperial Russian Navy Frigate Oslyabya.

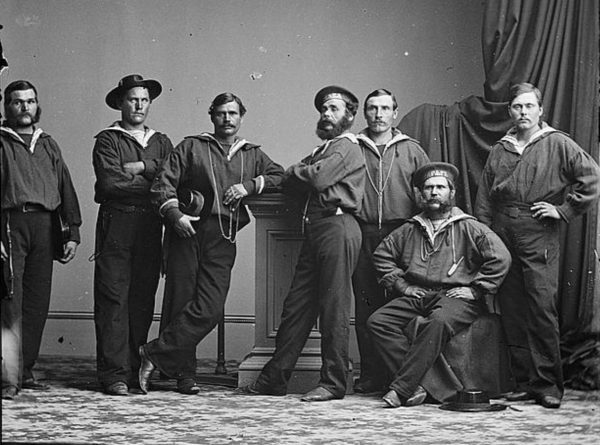

Here, courtesy of the Library of Congress, we see the faces of some of the Russian sailors who visited New York City:

Only one of these graves had been marked soon after the death of the sailor–that of Warrant Officer Borodovkin:

It is good to see these new markers, memorializing these sailors who have lain in unmarked graves at Green-Wood for more than 150 years. They died so far from home and were forgotten for so long. May these sailors, men of the Russian Navy, be remembered, and rest in peace.

I have just been reading about the Russian Ball in the diary of Maria Lydia Daly. I came here because I thought I remembered seeing something in Green-wood about the Russian sailors. Thank you for the info!

It’s a very interesting story–and relevant to today. The Czar was concerned that Crimea might try to secede–and thought that his best play was to send his fleets off to make clear that he opposed secession–whether by the American South or by Crimea.